New stowaway discovered in the bumblebee's gut

Vast biodiversity on a small scale: the ETH-Zurich researchers Regula Schmid and Martina Tognazzo have discovered and described a new parasite in important pollinators that can only be distinguished from its sister species genetically and by its size.

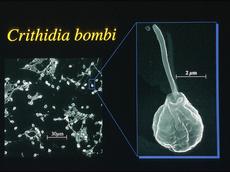

We won’t be discovering and describing many more big animals in Switzerland. The same can’t be said of when we peer through the microscope into the world of the protozoa, however. Regula Schmid and Martina Tognazzo from the Institute of Integrative Biology at ETH Zurich have described a new species in the Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology: a protozoan from the trypanosome family called Crithidia expoeki*.

The single-cell organism lives in the intestine of the large earth bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) and is a “descendant” of Crithidia bombi, a parasite which wasn’t discovered all that long ago itself, only having been described for the first time in 1987 and 1988.

Almost only distinguishable genetically

The two ETH-Zurich researchers stumbled across the new species more by chance than anything else. During genetic analyses, they realised that C. bombi colonises the bumblebee gut in two distinguishable lineages. In fact, the difference in the genetic material, especially in the mitochondrial DNA, was so pronounced that both lineages merited species status. The two species also differ significantly from another crithidia species, C. mellificae from the honey bee, which the researchers compared the bumblebee parasites with.

To the naked eye, however, the species can hardly be told apart – one reason why only genetic tests revealed the correct species they belonged to. That said, C. expoeki is slightly larger than C. bombi, as measurements conducted on the protozoa demonstrated.

Unpleasant squatters

Both species inhabit the intestine of bumblebees and can be found in the same individual. The parasites spread in the bumblebees’ excrement. Consequently, there is a risk of infection both in the nest and on flowers, where the bumblebees leave their excrement while looking for nectar. The parasites can live outside the intestine for several hours and survive the winter in the young queen bumblebee. Then, in the spring, no sooner has she started her own colony than they begin to spread and reproduce.

The ICrithidia infection rate among bumblebees is relatively high. In the spring, one in ten queens is affected before she starts her own colony. On average, about a third of the workers in a population are infected, but in extreme cases it can be as much as 80 percent.

The infestation doesn’t do the bumblebees much good. In lab experiments, infected queens are barely able to start a colony. And if the workers become malnourished due to long stretches of bad weather, for instance, the infected individuals die sooner than non-infected ones. As the Crithidia affect almost all species of bumblebee, the parasites are threatening the crucial pollination function they perform in nature.

Versatile clones

The parasites primarily reproduce clonally. Every bumblebee colony and every single animal possesses its own “cocktail” of crithidia clones, which ultimately leads to a wide diversity within the species found. “So far, we’ve identified over 200 different C. bombi clone lineages”, says Regula Schmid. However, she presumes that the parasites sometimes exchange genes, too; that’s the only explanation for the extreme genetic diversity. Just how the protozoa do so, however, is still unclear. “So far, we’ve only found cells with a double genotype; never haploids with only one set of genes”, stresses the researcher. It might be that the protozoa join up, exchange genes and separate again. Should this theory be confirmed, it would be a world first for this kind of directly transmitted insect parasites.

The two pathogens are found all over the world. They have also reached new areas because the large earth bumblebee – either naturally or introduced by man – has also spread. Breeders from Belgium and the Netherlands in particular sent their bumblebees all over the world, where the industrious insects were used as pollinators in agricultural cultures. They also took the single-celled parasites with them as stowaways. In North America, for example, a dramatic decline has been observed in bumblebees for some time now. This could be due to the crithidia introduced. “Breeders are more vigilant nowadays, however, to ensure the parasites aren’t transported inadvertently”, says Regula Schmid. Mexico has even banned the importation of large earth bumblebees.

“Illustrious“ relatives

The Crithidia species belongs to the trypanosomes, which play a major role as pathogens in humans and animals. The most well-known and by now well-researched of them is Trypanosoma brucei, the pathogen for sleeping sickness that is transmitted in the bite of the tsetse fly. Leishmaniosis, which is rife in South America, is also caused by a species of trypanosome.

So Regula Schmid isn’t all that surprised she has still managed to discover new species in bumblebees. There are numerous undescribed species, especially among the single-cell creatures, and using molecular techniques organisms could emerge as separate species that cannot be distinguished morphologically.

The Crithidia genus might also be transferred to the Leptomonas genus. “We’re still a long way from clarifying the taxonomy of trypanosome protozoa right down to the last detail”, she explains.

References

Schmid-Hempel R & Tognazzo M. Molecular Divergence Defines Two distinct Lineages of Crithidia bombi (Trypanosomatidae); Parasites of Bumblebees. 2010. The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. DOI: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2010.00480.x

* In honour of the workgroup Experimentelle Oekologie (experimental ecology) at ETH Zurich

READER COMMENTS